4

Hearing Speech

- 4.1 Speech as a Dynamic Stimulus

- 4.2 Categorical Perception of Speech Sounds

- 4.3 Subcortical Representations of Speech Sounds and Vocalizations

- 4.4 Cortical Areas Involved in Speech Processing: An Overview

- 4.5 The Role of Auditory Cortex: Insights from Clinical Observations

- 4.6 The Representation of Speech and Vocalizations in Primary Auditory Cortex

- 4.7 Processing of Speech and Vocalizations in Higher-Order Cortical Fields

- 4.8 Visual Influences

- 4.9 Summary

How our auditory

system supports our ability to understand speech is without a doubt one of the

most important aspects of hearing research. Severe hearing loss often brings social

isolation, particularly in those who were not born into deaf communities. For

most of us, the spoken word remains the primary communication channel,

particularly for the intimate, face-to-face exchanges and conversations that we

value so much. Naturally, we hope that, in due course, a better understanding

of the neurobiology of speech processing will improve our ability to repair

problems if this system goes wrong, or may allow us to build artificial speech

recognition systems that actually work, computers that we could actually talk

to. But while the potential rewards of research into the auditory processing of

speech are great, considerable technical and conceptual challenges also slow progress

in this area.

One major challenge stems from the

great complexity of speech. Essentially, a relatively modest number of speech

sounds (sometimes called “phones”) are recombined according to rules of

morphology to form words, and the words are recombined according to the rules

of grammar to form sentences. Our auditory brain can analyze the sound of any

sentence in a language we have learned, and decipher its meaning, yet the

number of correct, meaningful sentences in any language is so large as to be,

for all practical intents and purposes, infinite. Thus, when we learn a

language, we must not only acquire a sizeable lexicon of sound to meaning

mappings, but also perfect our grasp of the rules of morphology and grammar,

which allow us to manipulate and recombine the speech sounds to generate

endless varieties of new meanings.

Many animal species use

vocalizations to communicate with members of their own species, and sometimes

these communication sounds can be quite elaborate—consider, for example,

certain types of bird song, or the song of humpback whales. Nevertheless, the

complexity of human speech is thought to have no equal in the animal kingdom.

Dogs and some other domestic animals can be trained to understand a variety of

human vocal commands, and rhesus monkeys in the wild are thought to use between

thirty and fifty types of vocalization sounds to convey different meanings. The

number of different vocalizations used in these examples of

inter- and intraspecies vocal communication

is, however, fairly modest compared to the size of a typical human language

vocabulary, which can comprise tens of thousand words.

Animals also seem to have only a

limited capacity for recombining communication sounds to express new concepts

or describe their relationships. Even the most monosyllabic of human teenagers

readily appreciates that the meaning of the sentence “John eats and then flies” is very different from that of “And then John eats flies,” even though

in both sentences the speech sounds are identical and only their order has

changed a bit. Human children seem to learn such distinctions with little

effort. But while you do not need to explain this difference to your child, you

would have a terribly hard time trying to explain it to your dog. Indeed, many

language researchers believe that humans must have an innate facility for

learning and understanding grammar, which other animals seem to lack (Pinker,

1994).

Given this uniquely high level of

development of speech and language in humans, some may argue that there is

little point in studying the neural processing of speech and speechlike sounds in nonhuman animals. However, the tools

available to study the neural processing of communication sounds in humans are

very limited. Work with humans depends heavily either

on lesion studies that attempt to correlate damage to particular brain areas

with loss of function, on noninvasive functional imaging techniques, or on the

rare opportunities where electrophysiological recording or stimulation

experiments can be incorporated into open brain surgery for the treatment of

epilepsy. Each of these methods has severe limitations, and the level of detail

that is revealed by microelectrode recordings in animal brains is, as we shall

see, still an invaluable source of complementary information.

But using animal experiments to

shed light on the processing of vocalizations is not merely a case of “looking

for the key where the light is.” Human speech almost certainly evolved from the

vocal communication system of our primate ancestors, and it evolved its great

level of complexity in what is, in evolutionary terms, a rather short period of

time. No one is quite certain when humans started to speak properly, but we

diverged from the other surviving great ape species some 5 million years ago,

and our brains reached their current brain size some 1 to 2 million years ago (no

more than 100,000 generations). During this period, human speech circuits almost

certainly arose as an adaptation and extension of a more or less generic,

rudimentary mammalian vocal communication system, and animal experiments can

teach us a great deal about these fundamental levels of vocalization

processing.

Speech can be studied on many levels,

from the auditory phonetic level, which considers the manner in which

individual speech sounds are produced or received, to the syntactic, which considers

the role of complex grammatical rules in interpreting speech, or the semantic,

which asks how speech sounds are “mapped onto a particular meaning.” As we have

seen, studies of animal brains are unlikely to offer deep parallels or insights

into syntactic processing in the human auditory system, but neural

representations of speech sounds or animal vocalizations on the auditory/phonetic

level are bound to be very similar from one mammal to the next. Most mammals

vocalize, and do so in much the same way as we do (Fitch, 2006). As we briefly

described in section 1.6, mammals vocalize by pushing air through their larynx,

causing their vocal folds to vibrate. The resulting sound is then filtered

through resonant cavities in their vocal tracts, to impart on it a

characteristic “formant” structure. (On the book’s web site you can find short video clips showing

the human vocal folds and vocal tract in action. <flag>) There are some

differences in detail, for example, humans have a relatively deep-sitting

larynx, which makes for a particularly long vocal tract, and may allow us to be

a “particularly articulate mammal” (Ghazanfar & Rendall, 2008), but the basic layout is essentially the

same in all mammals, and the sounds generated by the vocal tracts of different

types of mammals consequently also have much in common. These similarities are more

obvious in some cases than in others (few humans, for example, would be very

flattered to hear that they sound like a donkey), but at times they can be very

striking, as in the case of Hoover the talking harbor seal.

When vocalizing to communicate

with each other, animals also face some of the same challenges we humans have

to overcome to understand speech. For example, both human and animal

vocalizations are subject to a fair amount of individual variability. No two

humans pronounce the same word absolutely identically. Differences in gender,

body size, emotional affect, as well as regional accents can all change the

sound of a spoken word without necessarily changing its meaning. Similarly,

dogs who differ in size or breed can produce rather

different sounding barks, yet despite these differences they all remain

unmistakably dog barks. Even song birds appear to have pronounced “regional dialects”

in their songs (Marler and Tamura, 1962). One common

problem in the processing of human speech as well as in animal vocalizations is

therefore how to correctly identify vocalizations, despite the often very

considerable individual variability. The neural processes involved in

recognizing communication sounds cannot be simple, low-level feature

extractors, but must be sophisticated and flexible pattern classifiers. We

still have only a very limited understanding of how animal and human brains

solve this kind of problem, but in experimental animals, unlike in humans,

these questions are at least in principle amenable to detailed experimental

observation.

This chapter is subdivided into

seven sections. In the first two sections, we examine the acoustic properties

of speech in greater detail, consider how the acoustic

features of speech evolve in time, and how they are categorized into distinct

speech sounds. In the third section, we describe how speech sounds are thought

to be encoded in subcortical structures. Our

knowledge of these subcortical representations comes

exclusively from animal experiments. In the fourth part, we briefly review the

anatomy of the cortex, and in the fifth we summarize what clinical observations

have taught us about the role played by various parts of the human cerebral

cortex in speech processing. In the last two sections, we examine the roles of

primary and higher-order cortical fields in greater detail, in the light of

additional information from human brain imaging and animal experiments.

4.1 Speech as a Dynamic Stimulus

When one considers

speech as an auditory stimulus, one obvious question to ask is: Is speech

radically different from other sounds, and if so, in what way? In section 1.6,

we looked at the production of vocalization sounds, and we noted that the

physics of vocal sound production is not particularly unusual, and contains

nothing that might not have an equivalent in the inanimate world. (You may wish

to glance through section 1.6 quickly before you read on if it is not fresh in

your mind.) The harmonics in voiced speech sounds produced by the oscillating

vocal folds are not so different from harmonics that might be produced by

vibrating taut strings or reeds. Unvoiced fricatives are caused by turbulent

airflow through constrictions in the vocal tract, and they resemble the noises

caused by rushing wind or water in both the way they are created and the way

they sound. Resonant cavities in our vocal tract create the all-important formants

by enhancing some frequencies and attenuating others, but they operate just

like any other partly enclosed, air-filled resonance chamber. So if speech

sounds are, in many respects, fundamentally similar to other environmental sounds

and noises, we might also expect them to be encoded and processed in just the

same way as any other sound would be by neurons of the auditory system.

Nevertheless, listeners only

rarely mistake other environmental sounds for speech, so perhaps there is

something about speech that makes it characteristically speechlike,

even if it is not immediately obvious what this something is. Consider the

sound of wind rushing through some trees. It may contain noisy hissing sounds that

resemble fricative consonants (fffff-, sss-, shhh-like sounds), and it

may also contain more harmonic, vaguely vowel-like “howling.” But the pitch and

amplitude contours of these sounds of howling wind usually change only slowly,

much more slowly than they would in speech. Meanwhile, a small stream of water

dropping into a pond might trickle, gurgle, and splash with an irregular rhythm

rather faster than that of speech. Thus, it seems that speech has its own

characteristic rhythm. Speech sounds change constantly in a manner that is

fast, but not too fast, and somewhat unpredictable yet not entirely irregular.

But can we turn this intuition regarding possible characteristic rhythms of

speech into something more tangible, more quantifiable?

One way to approach this question

is to consider the mechanisms of speech production in a little more detail. A

good example of this type of analysis can be found in a paper by Steven

Greenberg (2006), in which he argues that the syllable may the most appropriate

unit of analysis for speech sounds. Based on a statistical analysis of a corpus

of spoken American English, he concluded that syllables consist of an optional

“onset” (containing between zero and three consonants), an obligatory “nucleus”

(a vowel sound, which can be either a monophthong

like the /a/ in “at,” or a diphthong, like the /ay/ in “may”), and an optional

“coda” (containing between zero and four consonants). A single English syllable

can therefore be as simple as “a” or as elaborate as “straights.” Greenberg

would argue that more “atomic” speech sound units, such as the phoneme, or

phone, are unreal in the sense that they have no independent existence outside

the syllabic framework. Furthermore, he points out that the information content

of consonants depends on the syllabic context. For example, onsets are more

informative than codas, as can be seen by the fact that consonants in the coda

can often be lost without any loss of intelligibility (consider the lost /d/ in

“apples an’ bananas”). Given the diversity of English syllables, it is

unsurprising that they can also vary considerably in their temporal extent.

English syllables are typically 100 to 500 ms long, and are characterized by an

“energy arc,” since the vowel nucleus is normally up to 40 dB more intense than

the consonants of the onset or the coda. Note that not all languages exhibit as

much phonetic diversity in their syllables as English. In spoken Japanese, for

example, onsets very rarely comprise more than a single consonant, and the only

commonly used coda to a syllable is an optional “n.” Consequently, in Japanese

there are only a few hundred possible syllables, while in English there are

many thousands, but the onset-nucleus-coda syllabic structure is clearly a

feature of both languages.

As mentioned in chapter 1,

engineers like to refer to changes in a signal over time as “modulations”, and

they distinguish two fundamental types: amplitude modulation (AM, meaning the

sound gets louder or quieter) and frequency modulation (FM, meaning the

frequency content of the sound changes). Greenberg’s observation of one energy

arc in every spoken syllable, and one syllable every few hundreds of milliseconds

or so would lead us to expect that speech sounds should exhibit marked AM at

modulation rates of a few Hertz. Is this expectation borne out? If you look at

spectrograms of spoken sentences, like those shown in figure 2.13A or figure

4.1A, you do, of course, notice that speech contains

plenty of both AM and FM. But it is not obvious, just from looking at the

spectrograms, what the properties of these modulations really are, or whether

speech exhibits characteristic modulations, which would be either particularly

prominent in spoken sentences or particularly important in carrying the

information encoded in the speech signal.

How best to identify and describe

the modulations that are characteristic of speech is an old and important

research question. One recent study by Elliott and Theunissen

(2009) sheds new light on this by analyzing and manipulating the modulation

spectra of speech. (At first glance, the concept of a modulation spectrum is

perhaps a little technical and abstract, but it is useful, so hang in there for

the next two pages or so.) Essentially, modulation spectra are the two-dimensional

Fourier transforms (2DTFs) of the signal’s spectrogram. This may appear

terrifyingly complicated to the uninitiated, but it is not quite as bad as all

that. The concept is illustrated in figure 4.1. Figure

4.1A shows the spectrogram of a spoken sentence. Recall

from section 1.3 that ordinary Fourier transforms express a one-dimensional

signal, like a sound, as a superposition (or sum) of a large number of suitably

chosen sine waves. The 2DFT does a very similar thing, by expressing a two-dimensional

“picture” as a superposition of sine wave gratings or “ripples.” Think of these

ripples as regular zebra stripes of periodically (sinusoidally)

increasing and decreasing amplitude.

Figure 4.1B illustrates this by showing how

regions within the spectrogram are well approximated by such ripples. Consider

the region delineated by the leftmost black elliptic contour in the spectrogram.

This patch contains a very obvious harmonic stack associated with one of the

vowel sounds in the sentence, and the regularly spaced harmonics can be well

approximated by a ripple with a matching spectral modulation rate, that is, stripes

of an appropriate spacing along the vertical, frequency, or spectral dimension.

In this conceptual framework, spectral modulations are therefore manifest as zebra

stripes that run horizontally across the spectrogram, parallel to the time axis, and a set of harmonics with a fundamental frequency of

200 Hz would thus be captured to a large extent by a spectral modulation with a

modulation rate of 5 cycles/kHz. Perhaps counterintuitively,

a lower-pitched sound, with harmonics spaced, say, every 100 Hz, would

correspond to a higher spectral modulation rate of 10 cycles/kHz, since low-pitched

sounds with lower fundamental frequencies can squeeze a larger number of

harmonics into the same frequency band.

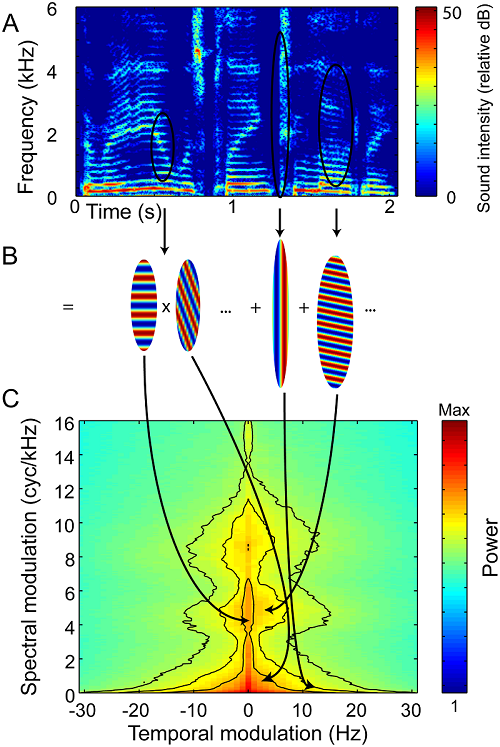

Figure 4.1

Modulation

spectra of spoken English. Spectrograms of spoken sentences (example sentence “The radio was

playing too loudly,” shown in A) are subjected to a two-dimensional Fourier

transform (2DFT) to calculate the sentence’s modulation spectrum (C). Just as

an ordinary Fourier transform represents a waveform as a superposition of sine

waves, a 2DFT represents a spectrogram as a superposition of “spectrotemporal ripples.” The spectrograms of the ripples

themselves look like zebra stripes (B). Their temporal modulation captures the

sound’s AM, and their spectral modulation captures spectral features such as

harmonics and formants.

Adapted from figure 1 of Elliott and Theunissen (2009) ) PLoS Comput Biol

5:e1000302.

But we cannot describe every

aspect of a spectrogram solely in terms of horizontal stripes that correspond

to particular the spectral modulations. There is also variation in time.

Particularly obvious examples are the short, sharp, broadband fricative and

plosive consonants which show up as vertical stripes in the spectrogram in figure

4.1A. In the modulation spectrum of a sound, these and

other “vertical” features are captured by “temporal modulations,” and this

occurs in a relatively intuitive manner. Temporal modulations simply measure

the amount of AM at some particular modulation rate, so high-frequency temporal

modulations capture fast changes in amplitude, low temporal modulation

frequencies capture slow changes in amplitude, and at 0 Hz temporal modulation

we find the sound’s grand average (constant) signal power.

Earlier, we mentioned that,

according to Greenberg (2006), speech sounds are characterized by syllabic energy

arcs, which are between 100 and 500 ms wide. These energy arcs should

correspond to temporal modulation frequencies between 10 and 2 Hz. The fact

that almost all the signal power in the speech modulation spectrum shown in figure

4.1C appears to be contained between +

and –10 Hz temporal modulation is therefore compatible with Greenberg’s

observations.

Hang on a minute. Did I just say a

temporal modulation of minus 10 Hz?

It is relatively easy to imagine what a temporal modulation of 10 Hz might

represent: Some property of the sound gets larger and then smaller and then

larger again ten times a second. But what, you may ask, is a temporal

modulation rate of minus 10 Hz

supposed to mean? You would be right to think that, in our universe, where time

never flows backward, a sound can hardly go thorough some cyclical changes once

every minus 0.1 s. Indeed, these “negative” temporal modulation frequencies

should simply be thought of as an expedient mathematical trick that allows us

to represent acoustic features in which frequency changes over time, and which

would show up as diagonal stripes in the spectrogram. The 2DFT captures such spectrotemporal modulations with diagonal ripples, and

these diagonals come in two flavors: They either rise, or they fall. In the

convention adopted here, a spectrotemporal ripple

with a negative temporal modulation corresponds to rising frequency

trajectories, while positive temporal frequencies correspond to falling

frequencies. The fact that the modulation spectrum shown in figure

4.1C is fairly symmetrical around 0 Hz

temporal modulation, thus, tells us that, in the sample of American English

sentences analyzed here, features with rising frequency content are just as

common as features with falling FM.

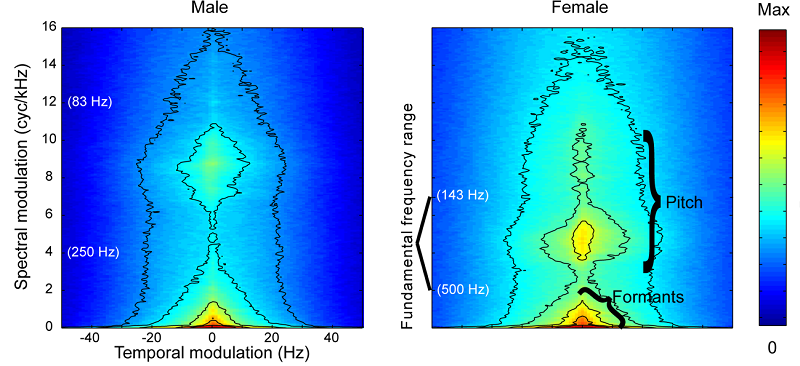

Figure 4.2

Modulation

spectra of male and female English speech.

From figure 2 of Elliott and

Theunissen (2009) PLoS Comput Biol 5:e1000302.

One very useful feature of the

modulation spectrum is that it separates out low spectral frequency, that is,

spectrally broad features such as the formants of speech, from high spectral

frequency features, such as harmonic fine structure associated with pitch. The

pitch of female speech tends to be noticeably higher than that of male speech,

but the formants of female speech differ less from those of male speech, which

presumably makes understanding speech, regardless of speaker gender,

substantially easier. This is readily apparent in the modulation spectra shown

in figure 4.2,

which are rather similar for the low spectral modulations (less than 3 cycles/kHz)

associated with the broad formant filters, but much more dissimilar for the

higher spectral modulations associated with pitch.

Given the crucial role of formants

in speech, we might therefore expect the meaning of the spoken sentence to be

carried mostly in the relatively low temporal and frequency modulations, and

one rather nice feature of Elliott and Theunissen’s

(2009) use of the modulation spectrum is that they were able to demonstrate

this directly. Modulation spectra, like ordinary Fourier transforms, are in

principle “invertible,” that is, you can use the spectrum to reconstruct the

original signal. Of course, if you blank out or modify parts of the modulation

spectrum before inversion, then you remove or modify the corresponding temporal

or spectral modulations from the original speech.

By testing comprehension of

sentences after filtering out various ranges of modulations, Elliott and Theunissen (2009) were able to demonstrate that spectral

modulations of less than 4 cycles/kHz and temporal modulations between 1 and 7

Hz are critical for speech intelligibility. They refer to this as the core region

of the human speech modulation spectrum, and it sits very much in those parts

of modulation space where we would expect the formants of speech to reside.

Filtering out modulations outside this core region has only a relatively small

effect on speech intelligibility, but may make it much harder to distinguish

male from female speakers, particularly if it affects spectral modulations

between 4 and 12 cycles/kHz, which, as we have seen in

figure 4.2,

encapsulate much of the differences in male versus female voice pitch. Examples

of such “modulation filtered” speech can be found in the online material accompanying

Elliott and Theunissen’s original (2009) paper, or on

the website accompanying this book. <flag>

Many artificial speech recognition

systems use a mathematical device that is conceptually closely related to the

modulation spectrum, known as the “dynamic cepstrum.”

Like the modulation spectrum, the cepstrum is

calculated as a Fourier transform along the frequency axis of the sound’s

spectrogram. The cepstrum can then be used to

separate out the low spectral modulations that are associated with the

relatively broadly tuned resonances of the vocal tract that mark the formants

of speech, and discard the high spectral modulations associated with pitch.

Pitch, thus, seems to add little

to speech comprehension, at least for English and most Indo-European languages.

(You can find examples of speech samples with altered pitch contours which

illustrate this on the book’s web site for <flag>). But it is worth

noting that many Asian languages are tonal, meaning that they may use pitch

trajectories to distinguish the meanings of different words. To give one

example: Translated into Mandarin Chinese, the sentence “mother curses the horse” becomes “ māma mà mă .” The symbols above the “a”s are

Pinyin1 tone markers, intended to indicate the

required pitch. Thus, the “ā” is

pronounced not unlike like the “a” in the English “bark,” but with a pitch much

higher than the speaker’s normal, neutral speaking voice. The “à,” in contrast, must be pronounced with

a rapidly falling pitch contour, and in the “ă”—particularly challenging for unaccustomed Western vocal

tracts—the pitch must first dip down low, and then rise again sharply, by well

over one octave, in a small fraction of a second. Remove these pitch cues, for

example, by filtering out spectral modulations above 7 cycles/kHz,

and the sentence becomes “mamamama,” which is gibberish in both Chinese and English.

One consequence of this use of pitch to carry semantic meaning in tonal

languages is that many current Western speech processing technologies, from

speech recognition software for personal computers to speech processors for

cochlear implants, are not well adapted to the needs of approximately one

quarter of the world’s population.

Nevertheless, even in tonal

languages, the lion’s share of the meaning of speech appears to be carried in

the formants, and in particular in how formant patterns change (how they are modulated)

over time. Relatively less meaning is encoded in pitch, but that does not mean

that pitch is unimportant. Even in Western, nontonal

languages, pitch may provide a valuable cue that helps separate a speech signal

out from background noise, or to distinguish one speaker from another. (We

shall return to the role of pitch as a cue in such auditory scene analysis

problems in chapter 6.) In chapter 3, we looked in detail at how pitch

information is thought to be represented in the auditory pathway, so let us now

look in more detail at how the auditory system distinguishes different classes

of speech sounds.

4.2 Categorical Perception of Speech Sounds

One crucial, but also

poorly understood, part of the neural processing of

speech is that sounds must be mapped onto categories. The physical properties

of a sound can vary smoothly continuously. Not only can we produce /a/ sounds

and /i/ sounds, but also all manner of vowels that

lie somewhere along the continuum between /a/ and /i/.

However, perceiving a sound as “between /a/ and /i/”

is unhelpful for the purpose of understanding speech. Our brains have to make categorical

decisions. A person who is talking to us may be telling us about his “bun” or

his “bin,” but it has to be one or the other. There is no continuum of objects

between “bun” and “bin.” Once we use speech sounds to distinguish different,

discrete objects, concepts, or grammatical constructs, we must subdivide the

continuous space of possible speech sounds into discrete categories. Such categorical

perception is therefore believed to be a key step in speech processing, and it

has attracted much interest among researchers. What are the criteria that our

brains use to distinguish sound categories? Are category boundaries arbitrary

parcellations of the set of all possible speech sounds, and do different

languages draw these boundaries differently? Or are there physical or

physiological laws that dictate where the boundaries should fall? And does the

human brain comprise specialized modules for recognizing such phoneme

categories that other animals lack, or is categorical

perception of speech sounds or vocalizations also seen in other animals?

Let us first consider the question

of phoneme boundaries. One thing that is readily apparent to most students of

foreign languages is that the phoneme boundaries are not the same in all languages.

German, for example, has its umlaut—“ä,” “ü,” and “ö”—effectively a set of

additional vowels that are lacking in English. Some Scandinavian languages have

even more vowels, such as the “å” and the “ø.” Thus, English lacks certain phoneme

categories that exist in other languages, but it also makes some distinctions other

languages do not. Japanese, for example, are famously unable to distinguish

between “r” and “l” sounds. This inability is not innate, however, but emerges

during the first year of life, as children are conditioned in their mother

tongue (Kuhl et al., 2006.). While these language-specific

differences suggest that phonetic boundaries are largely determined by the

environment we grow up in, they may nevertheless not be entirely arbitrary. In

a recent review, Diehl (2008) discussed two theories, the quantal

theory and the dispersion theory, which may help explain why phonetic category

boundaries are where they are. Both theories emerge from considerations of the

physical properties and limitations of the vocal tract.

To get a feeling for the ideas

behind quantal theory, let us start with a simple

experiment that you can try yourself. Make a long “ssssssss”

sound, and then, while keeping the sound going, move the tip of your tongue

very slowly backward in your mouth so as to gradually change the sound from /s/

to /sh/. When the tip of your tongue is near your

teeth, you will make an /s/, and with the tip of your

tongue further back against your palate you will make a /sh/.

So far so good, but you may notice that placing your tongue halfway between the

/s/ and /sh/ positions does not easily produce a

sound halfway between /s/ and /sh/. As you move your

tongue steadily forward or backward you may notice a very sudden transition (a “quantum

leap”) from /s/ to /sh/ or from /sh/

to /s/. Quantal theory posits that languages avoid

using speech sounds that are very close to such quantal

boundaries in the acoustics. We do not use speech sounds somewhere between /s/

and /sh/ because they would be too difficult to

pronounce reliably. Near a quantal boundary, a small

inaccuracy in the placement of the articulators will often lead to

disproportionately large changes in the sound produced, and therefore any

category of speech sounds that happened to live very close to a quantal boundary would be particularly easy to mispronounce

and mishear. Making sure that speech sound categories keep a respectful distance

from quantal boundaries would therefore make speech

more robust.

Dispersion theory (Liljencrants & Lindblom, 1972)

takes a different approach. It starts from the realization that there are

limits to the range of speech sounds a normal human vocal tract can produce.

The theory then makes the not unreasonable assumption that, to make speech

sound categories easily distinguishable, they should be widely spread out

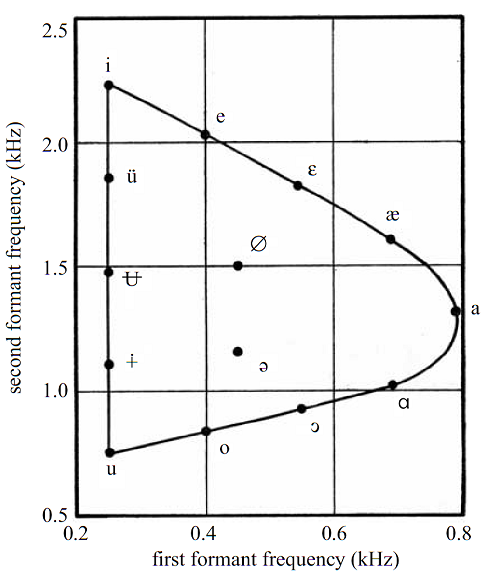

(dispersed) across this space of all possible speech sounds. Figure

4.3 illustrates this for the case of vowel sounds. The

coordinate axes of figure 4.3

show the first and second formant frequency of a particular vowel. The

continuous contour shows the limits of the formant frequencies that a normal

human vocal tract can easily produce, while the dots show first and second

formant frequencies for some of the major vowel categories of the world’s

languages. It, indeed, looks as if the vowels are not positioned randomly

inside the space available within the contour, but instead are placed so as to

maximize their distances, which should help make them easily distinguishable.

Figure 4.3

The contour shows the

pairings of possible F1/F2 formant frequencies, which are as distinct as they

could be, given the physical constraints of the human vocal tract. Symbols show

approximately where vowels of the world’s languages are located in this F1/F2

space.

Adapted from figure 7 of Diehl (2008)

Phil Trans Royal Soc B: Biological Sciences 363:965, with permission from the

Royal Society..

Thus, the quantal

and dispersion theories establish some ground rules for where phonetic category

boundary might fall, but there is nevertheless considerable scope for different

languages to draw up these boundaries differently, as we have seen. And this

means that at least some phoneme boundaries cannot be innate, but must be

learned, typically early in life. Interestingly, the learning of some of these

categorical boundaries appears to be subject to so-called critical or sensitive

developmental periods (Kuhl et al., 2008), so that

category distinctions that are learned in the early years of life are very hard

or impossible to unlearn in adulthood. Thus, Japanese speakers who have not

learned to differentiate between “r” and “l” early in life appear to find it

very difficult even to hear a difference between these sounds in adulthood. (We

will say more about sensitive periods in chapter 7.) However, that seems to be

an extreme case, and most learned phoneme boundaries do not bring with them an

inability to distinguish sounds that fall within a learned class. Thus, the

English language has no category boundary that distinguishes the vowels /ä/ or

/å/, yet adult native English speakers can learn very quickly to distinguish

and to recognize them.

So some phonetic category

boundaries, such as those between /r/ and /l/ or between /a/, /ä/, and /å/, are

therefore largely language specific and culturally determined, and children

pick them up in early infancy. But other phoneme boundaries seem fixed across many

languages, and may therefore be based on distinctions that are hard-wired into

the auditory system of all humans, or perhaps all mammals. For example, you may

recall that consonants differ either in their place or the manner of

articulation. Thus, /p/ and /t/ are distinguished by place of articulation (one

is made with the lips, the other with the tip of the tongue placed against the

top row of teeth), but /b/ and /p/ both have the same “labial” place of

articulation. What distinguishes /b/ from /p/ is that one is said to have a

“voiced” manner of articulation while the other is “unvoiced,” in other words

the /p/ in “pad” and the /b/ in “bad” differ mostly in their “voice onset time”

(VOT).2 In “pad,” there is a little gap of about 70

ms between the plosive /p/ sound and the onset of the vocal fold vibration that

mark the vowel /a/, while in “bad,” vocal fold vibration starts almost

immediately after the /b/, with a gap typically no greater than 20 ms or so.

Consequently, it is possible to morph a recording of the word “bad” to sound

like “pad” simply by lengthening the gap between the /b/ and the /a/. What is

curious about VOTs is that the length of VOTs does not seem to vary arbitrarily from one language to

the next. Instead, VOTs occur in no more than three distinct

classes, referred to as leading, short or long, which are conserved across the

world’s languages. In the leading category, voicing may start at about 100 ms

before the consonant, while short VOTs imply that

voicing starts 10 to 20 ms after the consonant, and long VOTs

mean that voicing starts about 70 ms after the consonant (Lisker

& Abramson, 1964). Leading voicing is not a typical feature of English, but

it is common in other languages such as Spanish, where, for example, “v” is

pronounced like a very soft /b/, so that the word “victoria” is pronounced “mbictoria.”

Several studies have shown that

animals, such as chinchillas (Kuhl & Miller 1978)

or quail (Kluender, Diehl, & Killeen, 1987), can be easily trained to discriminate stop consonants

with short or long VOTs. Thus the three VOT

categories may be “linguistic universals” because they are based on acoustic

distinctions that are particularly salient for the auditory systems not just of

humans but also of other animals.

4.3 Subcortical Representations of Speech Sounds and Vocalizations

You may recall from section

2.4, and in particular from figure 2.13, that the

inner ear and auditory nerve (AN) are thought to operate like a filter bank,

and firing rates along the tonotopic array of the

auditory nerve fiber bundle create a sort of “neurogram,”

a rate-place code for the acoustic energy distribution in the incoming sound.

The frequency resolution in that tonotopic rate-place

code is not terribly sharp, but it is easily sharp enough to capture formant

peaks. When we introduced the neurogram notion in figure

2.13, however, we did gloss over a small complication, which we now ought to

come clean about. We mentioned only in passing in section 2.4 that the majority

(roughly 80%) of AN fibers are high spontaneous rate

fibers that saturate—that is, they cannot fire any faster, once the sound at

their preferred frequency reaches a level of between 30 and 50 dB SPL. Over 30

years ago, Young and Sachs (1979) had already pointed out that this rate

saturation can have awkward consequences for the place-rate representation of

formants in the auditory nerve. Figure 4.4

illustrates some of their findings from a set of experiments in which they

recorded AN responses to artificial vowel sounds presented

at different sound levels.

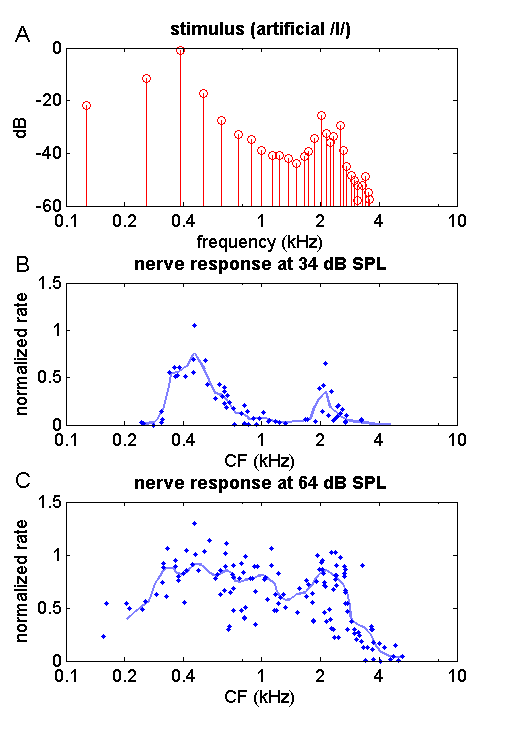

Figure 4.4

Responses

in the auditory nerve of the cat to a steady-state artificial vowel /I/. (A) power

spectrum of the vowel sound. It exhibits harmonics every 128 Hz, and formants

at approximately 0.4, 2, and 2.8 kHz. (B) Nerve fiber responses when the vowel

is presented at a relatively quiet 34 dB SPL. Each dot is the normalized evoked

firing rate of a single nerve fiber, plotted against each fiber’s CF. The

continuous line is a moving average along the frequency axis. The observed

nerve discharge rate distribution exhibits clear peaks near the stimulus

formant frequencies. (C) Nerve fiber responses when the sound is presented at a

moderately loud 64 dB SPL. Due to saturation of nerve fiber responses, the

peaks in the firing distributions are no longer clear. Based

on data published in Young and Sachs (1979).

Figure 4.4A shows the power spectrum of the

stimulus Sachs and Young used: an artificial vowel with harmonics every 128 Hz,

passed through a set of formant filters to impose formant peaks at about 400 Hz,

as well as at about 2,000 and 2,800 Hz. The resultant sound is not too different

from the human vowel /I/ (a bit like the “i” in

“blitz”). Note that the figure uses a logarithmic frequency axis, which

explains why the harmonics, spaced at regular 128-Hz intervals, appear to

become more densely packed at higher frequencies. Sachs and Young recorded

responses from many AN fibers in the anesthetized cat

to presentations of this sound at various sound levels. Figure

4.4B summarizes their

results for presentations of the artificial vowel at an

intensity of 34 dB SPL. Each point in figure

4.4B shows the response for a single nerve fiber.

The x-coordinate shows the nerve fiber’s characteristic frequency (CF), and the

y-coordinate shows the nerve fiber’s firing rate, averaged over repeated

presentations of the stimulus at 34 dB SPL, and normalized by subtracting the

nerve fiber’s spontaneous firing rate and dividing by the nerve fiber’s maximal

firing rate in response to loud pure tones at its CF. In other words, a normalized

rate of 0 means the neuron fires no more strongly than it would in complete

quiet, while a normalized rate of 1 means it fires almost as strongly as it

ever will. The gray continuous line in figure

4.4B shows a moving average across the observed

normalized firing rates for the AN fibers. This

averaged normalized firing rate as a function of CF appears to capture the

formant peaks in the stimulus quite nicely. So what’s the problem?

The problem is that 34 dB SPL is

really very quiet. Just the background hum generated by many air conditioning

systems or distant traffic noise will have higher sound levels. Most people

converse with speech sounds of an intensity closer to 65 to 70 dB SPL. But when

Sachs and Young repeated their experiment with the artificial vowel presented

at the more ”natural” sound level of 64 dB SPL, the firing rate distribution in

the auditory nerve was nothing like as pretty, as can be seen in figure 4.4C. The firing rate

distribution has become a lot flatter, and the formant peaks are no longer

readily apparent. The problem is not so much that the peaks in the firing rate

distribution at the formants have disappeared, but rather that the valley

between them has filled in. This is a classic example of the so-called dynamic

range problem. Most AN fibers saturate at relatively

modest sound intensities, and sounds don’t have to become very loud before the

AN fibers lose their ability to signal spectral contrasts like those between

the formant peaks and troughs in a vowel.

The curious thing, of course, is

that even though the representation of the formant peaks across the nerve fiber

array appears to become degraded as sound levels increase, speech sounds do not

become harder to understand with increasing loudness—if anything the opposite

is true. So what is going on?

There are a number of possible

solutions to the dynamic range problem. For example, you may recall from

chapter 2 that AN fibers come in two classes: High

spontaneous rate (HSR) fibers are very sensitive and therefore able to respond

to very quiet sounds, but they also saturate quickly; low spontaneous rate

(LSR) fibers are less sensitive, but they also saturate not nearly as easily.

The plots in figure 4.4

do not distinguish between these classes of AN fibers.

Perhaps the auditory pathway uses HSR fibers only for hearing in very quiet

environments. HSR fibers outnumber LSR fibers about four to one, so the large

majority of the nerve fibers sampled in figure

4.4 are likely to be HSR fibers, and using those to

encode a vowel at 64 dB might be a bit like trying to use night vision goggles

to see in bright daylight.

Young and Sachs (1979) also

proposed an alternative, perhaps better explanation when they noticed that,

even though the nerve fibers with CFs between 300 and

3,000 Hz shown in figure 4.3C may all fire at similarly high

discharge rates, they tend to phase lock to the formant frequencies close to

their own CF. For example, you might find a 500-Hz fiber that is firing

vigorously, but at an underlying 400-Hz rhythm. In that case you might conclude

that the dominant frequency component in that frequency range is the frequency

signaled by the temporal firing pattern (400 Hz) even if this is not the nerve

fiber’s preferred frequency (500 Hz). Such considerations led Young and Sachs

(1979) to propose a response measure that takes both firing rate and phase

locking into account. This response measure, the “average localized synchronized

rate” (ALSR), quantifies the rate of spikes that are locked to the CF of the

neuron. In the previous example, the ALSR would be rather low for the 500-Hz

neuron, since most spikes are synchronized to the 400-Hz formant. The ALSR

measure of auditory nerve discharges reflects formant frequencies much more

stably than ordinary nonsynchronized rate-place codes

could.

Whether your auditory brainstem

solves the dynamic range problem by computing the ALSR, by listening

selectively either to HSR or to LSR fibers depending on sound level, or by

relying on some other as yet unidentified mechanism is not known. However, we

can be pretty certain that your auditory brainstem does solve this problem, not

only because your ability to understand speech tends to be robust over wide

sound level ranges, but also because electrophysiological recordings have shown

that so-called chopper neurons in the ventral cochlear nucleus can represent

formants in a much more sound level invariant manner than the auditory nerve

fibers do (Blackburn & Sachs, 1990).

At the level of the auditory

brainstem, as well is in the major midbrain nuclei such as the inferior colliculus or the medial geniculate,

and to some extent even in primary auditory cortex, this representation is

thought to retain a somewhat spectrographic character. The pattern of neural

discharges mostly reflects the waxing and waning of acoustic energy in the

particular frequency bands to which these neurons happen to be tuned. But much

experimental evidence suggests that this representation is not very isomorphic,

in the sense that neural firing patterns in the brainstem and midbrain do not

simply and directly reflect the rhythms of speech. Nor do the temporal response

properties of neurons in the midbrain or cortex appear to be tuned to match the

temporal properties of speech particularly well. Evidence for this comes from

studies like those by Miller and colleagues (2002), who have analyzed response

properties of midbrain and cortex neurons using synthetic dynamic ripple

stimuli and reverse correlation. The dynamic ripple sounds they used are

synthetic random chords that vary constantly and randomly in their frequency and

amplitude. The rationale behind these experiments rests on the assumption that,

at some periods, just by chance, this ever changing stimulus will contain

features that excite a particular neuron, while at other times it will not. So,

if one presents a sufficiently long random stimulus, and then asks what all

those stimulus episodes that caused a particular neuron to fire had in common,

one can characterize the neuron’s response preferences. Often this is done by a

(more or less) simple averaging of the spectrogram of the stimulus episodes

that preceded a spike, and the resulting spike-triggered average of the

stimulus serves as an estimate of the neuron’s spectrotemporal

receptive field (STRF).

You may recall from our

discussions in chapter 2 that auditory neurons can be modeled, to a coarse

approximation, as linear filters. For example, in figure 2.12, we illustrated

similarities between auditory nerve fibers and so-called gamma-tone filters.

Now, in principle, we can also try to approximate auditory neurons in the

central nervous system with linear filter models (only the approximation risks

becoming ever cruder and more approximate as each level of neural processing

may contribute nonlinearities to the neural response properties). The way to

think of a neuron’s STRF is as a sort of spectrographic display of the linear

filter that would best approximate the neuron’s response properties.

Consequently, we would expect a neuron to fire vigorously only if there is a

good match between the features of the STRF and the spectrogram of the

presented sound.

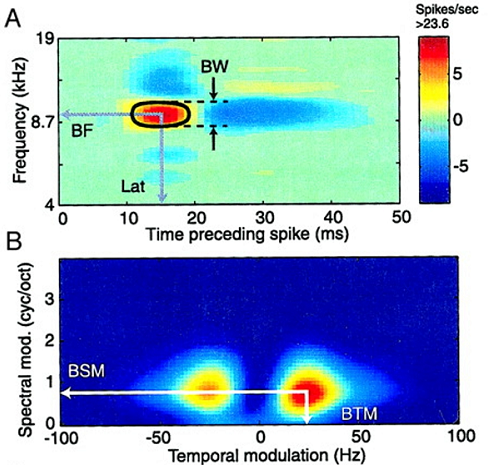

Figure 4.5A shows such an example of an STRF

estimated for one neuron recorded in the auditory midbrain of the cat. The STRF

shows that this particular neuron is excited by sound at about 9 kHz and the

excitation kicks in with a latency of about 10 ms.

There are inhibitory frequency regions both above and below the neuron’s

preferred frequency. But we also see that the excitatory region near 9 kHz is followed

by “rebound inhibition,” which should shut off this neuron’s firing after about

30 ms of response. The STRF would thus predict that continuous, steady-state

sounds are not particularly effective stimuli for this neuron.

In section 4.1, we discussed the

dynamic properties of speech, and saw how its characteristic amplitude and

frequency modulations can be captured by its modulation spectrum. We also saw how

the modulation spectrum is generated from the sound’s spectrogram by two-dimensional

Fourier transformation. Now, if the STRF of a neuron is a sort of

spectrographic display of the spectral and temporal features that a neuron

prefers, we ought to be able to apply a similar thought process here, and

transform the neuron’s STRF with a 2DFT to reveal what sort of spectral and

temporal modulations the neuron might respond to with particular vigor. To use

the technical term, we can use the 2DFT of the STRF to obtain the neuron’s “modulation

transfer function” (MTF). Figure 4.5B

shows the MTF obtained in this manner from the STRF shown in figure 4.5A.

Figure 4.5

(A) Spectrotemporal receptive field of a neuron recorded in the

auditory thalamus of the cat. BW: spectral band width, BF: best frequency, Lat:

response latency. (B) Modulation transfer function for the same neurons. BSM, best

spectral modulation, BTM, best temporal modulation.

Reproduced from figure 1 of Miller et

al. (2002), with permission from the American Physiological Society..

When many neurons are

characterized in this manner, it is possible to investigate what range of

temporal and spectral modulations the population of neurons, on average, might

be able to represent effectively through equivalent modulations of their own

firing rates. We can then ask, is this population MTF well

matched to the modulations encountered in speech? Figure

4.6 shows population MTFs

determined in this manner for the main auditory thalamic relay station to the

cortex, the ventral part of the medial geniculate (MGv), and for the primary auditor cortex of the cat.

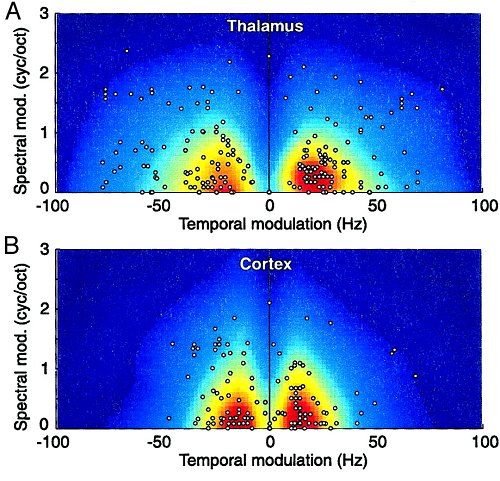

Figure 4.6

(A) Population MTF of

the auditory thalamus (MGv) cat. The dots show best

temporal and spectral modulation values for individual neurons. The gray values

show the averaged MTF. (B) Population MTF for cat A1.

Reproduced from figure

8 of Miller et al. (2002), with permission from the American Physiological

Society.

Comparing the population MTFs of auditory thalamus and cortex shown in figure 4.6 to the speech modulation

spectra shown in figures 4.1C and 4.2,

we notice that the neural MTFs at these, still

relatively early, auditory processing stations are not obviously well matched

to the temporal modulations characteristic of speech. However, it would

probably have been surprising if they were. For starters, the MTFs shown in figure

4.6 were recorded in cats, and the cat midbrain is

hardly likely to be optimized for the processing of human speech. However, we

have no reason to assume that the population MTFs of

human thalamus or primary auditory cortex would look much different. The shape

of the population MTF can provide some insights into the nature of the neural

code for sounds in the midbrain that are likely to be true for most mammals.

The best temporal modulation frequencies for these neurons are often higher

than they would need to be for the purposes of speech encoding (extending out

to 50 Hz and above while speech modulations rarely exceed 30 Hz). In contrast,

the best frequency modulations are not nearly high enough to capture the pitch

part of the speech modulation spectrum, but they do appear quite well matched

to the frequency modulation spectra of formants. We saw in chapters 2 and 3

that, already at the level of the auditory nerve, frequency tuning of individual

nerve fibers is not usually sharp enough to resolve the harmonics that would

reveal the pitch of a periodic sound, and the low-pass nature of the population

MTF suggests that midbrain neurons cannot resolve harmonics in the sound’s

spectrum either.

Another striking mismatch between

the speech modulation spectrum and the neural population MTF can be seen at

temporal modulation frequencies near zero. Speech modulation spectra have a lot

of energy near 0-Hz temporal modulation, which reflects the fact that, on

average, there is some sound almost all the time during speech. However, as one

ascends the auditory pathway toward cortex, auditory neurons appear

increasingly unwilling to respond to sustained sound with sustained firing.

Instead, they prefer to mark sound onsets and offsets with transient bursts of

firing, and then fall silent. Slow temporal modulations of their firing rates

are consequently rare. With this emphasis on change in the spectrum, rather

than sustained sound energy levels, the representation of sounds in the

midbrain and above resembles the derivative of the spectrogram with respect to

time, but since speech sounds are rarely sustained for long periods of time,

this emphasis on time-varying features does not change the representation

dramatically. In fact, as we shall see later, even at the level of the primary

visual cortex, speech sounds appear to be represented in a manner that is

perhaps more spectrographic (or neurographic) than

one might expect. Consequently, much interesting processing of speech remains

to be done when the sounds arrive at higher-order cortical fields. Where and

how this processing is thought to take place will occupy us for much of the

rest of this chapter.

4.4 Cortical Areas Involved in Speech Processing: An Overview

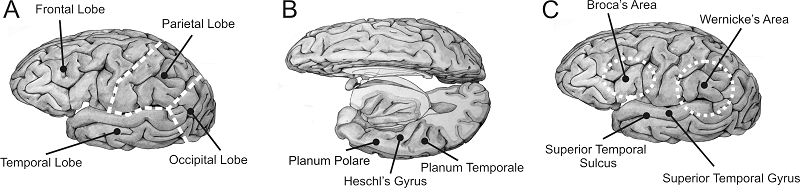

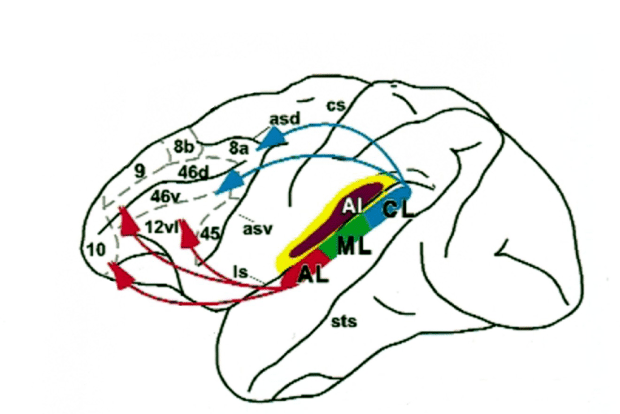

Before we start our

discussion of the cortical processing of speech sounds in earnest, let us

quickly revise some of the key anatomical terms, so we know which bit is which.

Figure 4.7 shows anatomical drawings of the human

cerebral cortex. Figure 4.7A

shows the left side of the cortex, reminding you that the cortex on each

hemisphere is subdivided into four lobes: The occipital lobe at the back deals

mostly with visual processing; the parietal lobe deals with touch, but also

integrates information across sensory modalities to keep track of the body’s

position relative to objects and events around us; the frontal lobe is involved

in planning and coordinating movements, short-term working memory, and other cognitive

functions; and, finally, the temporal lobe is involved in hearing, but also in

high-level vision, general object recognition, and the formation of long-term

memories.

In the human brain, many of the

auditory structures of the temporal lobe are not visible on the surface, but

are tucked away into the sylvian fissure, which forms

the boundary between the temporal, frontal and parietal lobes. Figure

4.7B

therefore shows a view of the human brain from above, with the left frontal and

parietal lobes cut away to show the upper bank of the temporal lobe. Most of

the auditory afferents from the thalamus terminate in Heschl’s

gyrus, where primary auditory cortex is found in

humans. To the front and back of Heschl’s gyrus lie the planum polare and the planum temporale, where second-order auditory belt areas are

situated.

Figure 4.7

(A) Drawing of a

lateral view of the human brain, showing the four principal lobes. (B) Human

cortex seen from above, with the frontal and parietal lobe cut away to expose

the superior bank of the temporal lobe, where the primary auditory cortex (Heschl’s gyrus) and auditory belt

areas (planum temporale and

polare) are situated. (C) Lateral view showing higher-order

cortical areas commonly associated with higher-order auditory processing and

speech.

Original artwork kindly provided by

Jo Emmons (www.joemmons.com).

But the processing of speech

certainly also involves cortical areas well beyond the auditory areas on the

upper bank of the temporal lobe. A few of the other key areas are shown in figure 4.7C,

including the superior temporal gyrus (STG) and sulcus (STS), and Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas. The latter two are both named after nineteenth-century

neurologists who associated damage to these areas with disturbances of either

speech production (Broca’s aphasia) or speech

comprehension (Wernicke’s aphasia. See the book’s

website for short video clips showing patients with Broca’s

and Wernicke’s aphasia.) Note that the definitions of

Broca’s and Wernicke’s

areas are not based on anatomical landmarks, but instead derived from case

studies of patients with injuries to these parts of the brain. Since the damage

caused by such injuries is rarely confined to precisely circumscribed regions, the

exact boundaries of Broca’s and Wernicke’s

areas are somewhat uncertain, although a consensus seems to be emerging among neuroanatomists that Broca’s area

should be considered equivalent to the cytoarchitectonically

defined and well-circumscribed Brodmann areas 44 and

45. In any case, both Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas clearly lie either largely or entirely

outside the temporal lobe, which is traditionally associated with auditory

processing. Note also that, while both hemispheres of the cortex have frontal,

parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes, as well as Heschl’s

gyri and superior temporal sulci,

much clinical evidence points to the left hemisphere playing a special role in

speech processing, and Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas appear normally to be confined largely or

wholly to the left hemisphere.

4.5 The Role of Auditory Cortex: Insights from Clinical Observations

Paul Broca, who lived from 1824 to 1880, and in whose honor one

of the brain areas we just encountered is named, was one of the first to

observe that speech processing may be asymmetrically distributed in cortex. He

stated that the left hemisphere was “dominant” for language. Broca chose his words carefully. The left hemisphere’s

dominance is not meant to imply that the right hemisphere contributes nothing

to speech comprehension or production. Rather, the left hemisphere, in most but

not all individuals, is capable of carrying out certain key speech processing

functions even if the right hemisphere is not available to help, but the right

hemisphere on its own would not succeed. We might envisage the situation as similar

to that of a lumberjack who, if forced to work with one hand only, would be

able to wield his axe with his right hand, but not with his left. This “righthand-dominant lumberjack” would nevertheless work at

his best if allowed to use both hands to guide his axe, and his left hand would

normally be neither idle nor useless.

Since Broca’s

time, a wealth of additional clinical and brain imaging evidence has much

refined our knowledge of the functional roles of the two brain hemispheres and

their various areas in both the production and the comprehension of speech.

Much of that work was nicely summarized in a review by Dana Boatman (2004),

from which we present some of the highlights.

Much of the research into human

speech areas has been driven forward by clinical necessity, but perhaps

surprisingly not as much from the need to understand and diagnose speech

processing deficits as from the desire to cure otherwise intractable epilepsy

by surgical means. In these epilepsy surgeries, neurosurgeons must try to

identify the “epileptic focus,” a hopefully small piece of diseased brain

tissue that causes seizures by triggering waves of uncontrollable hyperexcitation which spread through much of the patient’s

brain. Successful identification and removal of the epileptic focus can cure

the patient of a debilitating disease, but there are risks. For example, if the

operation were to remove or damage one of the brain’s crucial speech modules, the

patient would be left dumb or unable to understand speech. That would be a

crippling side effect of the operation one would like to avoid at all cost. So,

the more we know about the location of such crucial brain regions, the better the

surgeon’s chances are to keep the scalpel well away from them.

One complicating factor which neurosurgeons

have appreciated for a long time is that the layout of cortex is not absolutely

identical from one person to the next, and it is therefore desirable to test each

individual patient. One such test that has been administered frequently since

the 1960s is the so-called Wada procedure (Wada & Rasmussen, 1960), during

which a short-acting anesthetic (usually sodium amytal)

is injected into the carotid artery, one of the main blood supply routes for

the cerebral hemispheres of the brain. After injecting the anesthetic on either

the left or right side only, one can then try to have a conversation with a

patient who is literally half asleep, because one of his brain hemispheres is

wide awake, while the other is deeply anesthetized. Records of such Wada tests

have revealed that approximately 90% of all right-handed patients and about 75%

of all left-handed patients display Broca’s classic

“left hemisphere dominance” for speech. The remaining patients are either

“mixed dominant” (i.e., they need both hemispheres to process speech) or have a

“bilateral speech representation” (i.e., either hemisphere can support speech

without necessarily requiring the other). Right hemisphere dominance is

comparatively rare, and seen in no more than 1 to 2% of the population.

The Wada procedure has its

usefulness—for example, if we needed to perform surgery on the right brain

hemisphere, it would be reassuring to know that the patient can speak and

comprehend speech with the spared left hemisphere alone. However, often one

would like more detailed information about the precise localization of certain

functions than the Wada test can provide. To obtain more detailed information,

neurosurgeons sometimes carry out electrocortical

mapping studies on their patients. Such mappings require preparing a large part

of one of the patient’s brain hemispheres for focal electrical stimulation

either by removing a large section of the skull to make the brain accessible

for handheld electrodes, or by implanting a large electrode array over one of

the hemispheres. During the actual mapping, the patient receives only local

anesthetic and analgesics, and is therefore awake and can engage in

conversation or follow simple instructions.

The patients are then tested on

simple speech tasks of varying level of complexity. The simplest, so called acoustic-phonetic

tasks, require only very simple auditory discriminations; for example, the

patient is asked whether two syllables presented in fairly quick succession are

the same or different. The next level, so called phonological tasks, require a slightly deeper level of analysis of the

presented speech sounds. For example, the patient might be asked whether two

words rhyme, or whether they start with the same phoneme. Note that neither acoustic-phonetic nor phonological tasks requires

that the tested speech sounds be understood. For example, I can easily repeat

the syllable “shmorf,” I can tell that it rhymes with

“torf,” and that “shmorf”

and “torf” do not start with the same phoneme. I can

do all this even though both “shmorf” and “torf” are completely meaningless to me. The ability to use

speech sounds for meaningful exchanges requires a further so-called lexical-semantic

level of analysis, which typically involves asking a patient to carry out

simple instructions (such as “please wiggle the ring finger on your left hand”)

or to answer questions of varying level of grammatical complexity.

While the patients are grappling

with these acoustic, phonological, or semantic tasks, the surgeon will sneakily

send small bursts of electric current to a particular spot on their brain. This

current is just large enough to disrupt the normal activity of the neurons in

the immediate vicinity of the stimulating electrodes, and the purpose of this

is to test whether this highly localized disruption makes any obvious

difference to the patient’s ability to perform the task.

In such electrocortical

mapping studies, one does observe a fair degree of variation from one patient

to another, as no two brains are exactly alike. But one can nevertheless observe

clear trends, and Dana Boatman (2004) has summarized which parts of cortex

appear to be essential for acoustic, phonological, or semantic tasks across a

large numbers of patients. The results of her analysis are shown in figure 4.8.

Figure 4.8

Sites

where acoustic (A), phonological (B), or lexical-semantic (C) deficits can be

induced by disruptive electrical stimulation. The light gray symbols show locations on perisylvian cortex that were tested by applying disruptive

electrical stimulation. The black symbols show sites where such stimulation

interfered with the patient’s ability to perform the respective task.

Reproduced from figures 1 through 3

of Boatman (2004),. Cognition 92:47-65., with

Copyright (2004) permission from Elsevier.

The data in figure 4.8 suggest a hierarchical

arrangement. The more complex the task, the larger the number

of cortical sites that seem to make a critical contribution because disruptive

stimulation at these sites impairs performance. Acoustic-phonetic tasks

(figure 4.8A)

are not easily disrupted. Only at a single spot on the superior temporal sulcus (STS) could electrical stimulation reliably

interfere with phonetic processing in all patients. Phonological processing (figure 4.8B) requires a greater

degree of analysis of the speech sounds, and it seems to involve large parts of

STS, as well as some points on Broca’s area on the

frontal lobe, since focal stimulation of any of these areas impairs

performance. Lexical-semantic tasks (figure

4.8C) are yet more complex, and seem to involve yet

more cortical territory because they are even more vulnerable to disruption.

Focal stimulation not just of the superior temporal gyrus

(STG), STS, and Broca’s area, but also of Wernicke’s area in the parietal lobe can disrupt the performance

of this type of tasks.

In figure

4.8 we also notice that the sites where one can

disrupt processing on the next higher level of complexity always appear to

include the sites that were involved in the lower processing levels. That is

perhaps unsurprising. If some focal electrical stimulation perturbs my

perception of speech sounds to the point where I can no longer tell whether two

words spoken in sequence were the same or different, then it would be odd if I

could nevertheless tell whether those word rhymed, or what they meant. XXX

The clinical data thus suggests a

cortical processing hierarchy, which begins with acoustic-phonetic processing

in or near primary auditory cortex, and engages ever-increasing amounts of

cortical territory as the brain subjects vocalizations

to phonological and semantic analysis. But the clinical data cannot provide

much detail on what exactly each particular cortical area contributes to the

process. For example, the fact that semantic processing of sounds can be

disrupted by electrical stimulation of parts of Wernicke’s

area does not mean that important steps toward this semantic processing may not

have already begun at much earlier levels in the cortical hierarchy. In fact,

some results from animal research might be interpreted as evidence for

“semantic preprocessing” from the earliest levels.

4.6 The Representation of Speech and Vocalizations in Primary Auditory Cortex

Since semantic

processing involves finding the “meaning” of a particular speech sound or

animal vocalization, one can try to investigate semantic processing by

comparing neural responses to “meaningful” sounds with responses to sounds that

are “meaningless” but otherwise very similar. One simple trick to make speech

sounds incomprehensible, and hence meaningless, is to play them backward. Time

reversing a sound does not change its overall frequency content. It will flip

its modulation spectrum along the time axis, but since speech modulation

spectra are fairly symmetrical around t

= 0 (see figure 4.1C), this does not seem to matter much. Indeed, if you have

ever heard time-reversed speech, you may know that it sounds distinctly speechlike, not unlike someone talking in a foreign

language (You can find examples of such time reversed speech in the book’s

website <flag>). Of

course, one can also time reverse the vocalizations of other animals, and

indeed, in certain songbird species, brain areas have been identified in which

neurons respond vigorously to normal conspecific songs, but not to

time-reversed songs (Doupe and Konishi,

1991). Typically, the songbird brain areas showing such sensitivity to time

reversal seem to play an important role in relating auditory input to motor

output, for example, when a bird learns to sing or monitors its own song.

Interestingly, Xiaoqin

Wang and colleagues (1995) have used the same trick in marmosets, a species of

new world monkey, and found that already in primary auditory cortex, many

neurons respond much more vigorously to natural marmoset twitter calls than to

time-reversed copies of the same call. Could it be that marmoset A1 neurons

fire more vigorously to the natural calls because they are “meaningful,” while

the time-reversed ones are not? If the same natural and time-reversed marmoset

calls are presented to cats, one observes no preferential responses in their A1

for the natural marmoset calls (Wang & Kadia,

2001), perhaps because neither the natural nor the reversed marmoset calls are

particularly meaningful for cats.

However, the interpretation of

these intriguing data is problematic. One complicating factor, for example, is

the fact that the relationship between the number of spikes fired by some

neuron during some relatively long time interval and the amount of information

or meaning that can be extracted from the neuron’s firing pattern is not

straightforward. A more vigorous response does not necessarily convey

proportionally more information. This was clearly illustrated in a study by Schnupp and colleagues (2006), who used the same marmoset

calls as those used by Wang et al. (1995), but this time played them either to

naïve ferrets, or to ferrets who had been trained to recognize marmoset twitter

calls as an acoustic signal that helped them find drinking water. For the

trained ferrets, the marmoset calls had thus presumably become “meaningful,”

while for the naïve ferrets they were not. However, neither in the naïve nor

the trained ferrets did primary auditory cortex neurons respond more strongly

to the natural marmoset calls than to the time-reversed ones. Instead, these

neurons responded vigorously to either stimuli, but many of these neurons

exhibited characteristic temporal firing patterns, which differed

systematically for different stimuli. These temporal discharge patterns were

highly informative about the stimuli, and could be used to distinguish

individual calls, or to tell normal from time-reversed ones. However, these

neural discharge patterns had to be “read out” at a temporal resolution of 20

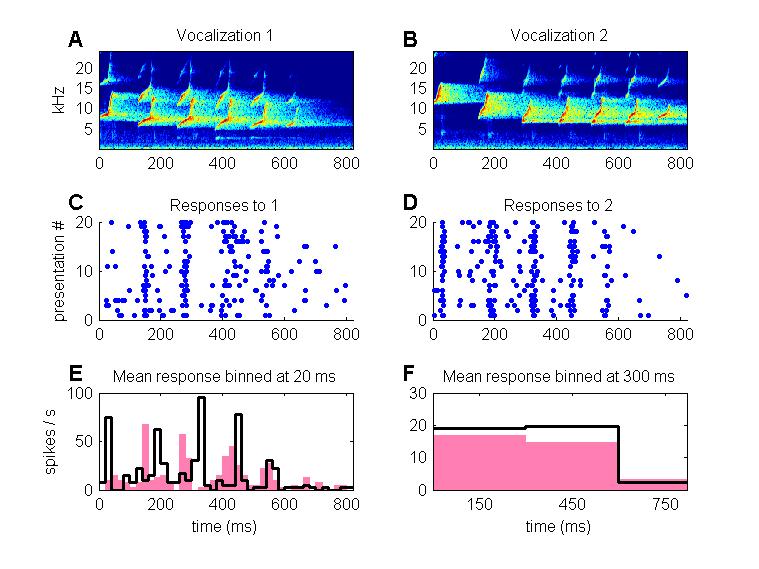

ms or finer; otherwise this information was lost. Figure

4.9 illustrates this. Schnupp

and colleagues (2006) also showed that training ferrets to recognize these

marmoset vocalizations did not change the nature of this temporal pattern code,

but did make it more reliable and hence more informative.

Figure 4.9

(A, B) Spectrograms of

two marmoset “twitter calls.” (C, D) Dot rasters showing responses of a neuron in ferret

primary auditory cortex to these sounds. Each dot represents one nerve impulse,

each row of dots an impulse train fired in response to a single presentation of

the corresponding stimulus. The neuron fires similar mean spike counts but with

different temporal discharge patterns in response to each stimulus. (E, F)

Responses shown in C and D are plotted as histograms, showing the mean firing

rate poststimulus onset, with the responses to

stimulus 1 shown in gray, those to stimulus 2 in black. At fine temporal

resolutions (small histogram bin width, e.g., 20 ms shown in E) the differences

in the response patterns are very clear and, as shown by Schnupp

et al. (2006), contain much information about stimulus identity. However, at

coarser temporal resolutions (300 ms bin width, shown in F), the responses look

very similar, and information about stimulus identity is lost.

These results indicate that the

representation of complex stimuli like vocalization or speech at early stages

of the cortical processing hierarchy is still very much organized around

“acoustic features” of the stimulus, and while this feature-based

representation does not directly mirror the temporal fine structure of the

sound with submillisecond precision, it does

nevertheless reflect the time course of the stimulus at coarser time

resolutions of approximately 10 to 20 ms. It may or may not be a coincidence

that the average phoneme rate in human speech is also approximately one every

20 ms, and that, if speech is cut into 20-ms-wide strips, and each strip is

time-reversed and their order is maintained, speech remains completely

comprehensible (Saberi & Perrott,

1999) (A sound example demonstrating this can be found on the book’s website.

<flag>).

Further evidence for such a

feature-based representation of vocalizations and speech sounds in mammalian A1

comes from a recent study by Engineer and colleagues (2008), who trained rats

to recognize consonants of American English. The rats were trained to

distinguish nonsense syllables that differed only in their onset consonant:

“pad” from “bad,” “zad” from “shad,” “mad” from “nad,” and so on. Some of these distinctions the rats

learned very easily, while they found others more difficult. Engineer and

colleagues then proceeded to record responses to these same syllables from

hundreds of neurons in the auditory cortex of these animals. These responses

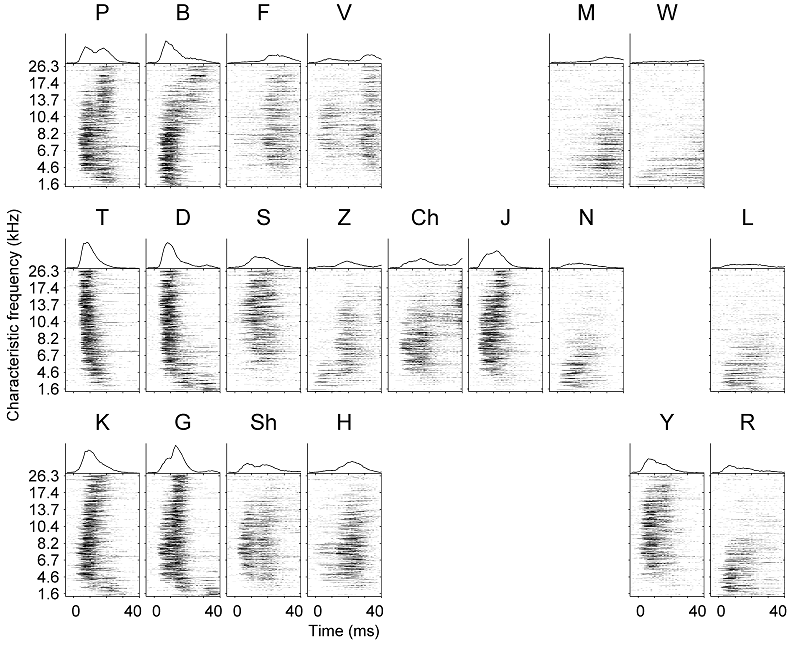

are reproduced here in figure 4.10 as neurogram-dot raster displays. Each panel shows the

responses of a large number of primary auditory cortex neurons, arranged by

each neuron’s best frequency along the y-axis. The x-axis shows time after stimulus

onset. The panels zoom in on the first 40 ms only to show the response to the

onset consonant.

Figure 4.10

Responses

or rat A1 neurons to 20 different consonants.

Adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers, Ltd: Nature

Neuroscience: Figs 1 and 2 of Engineer et al. (2008) Nat Neurosci

11:603-608., copyright (2008)

Figure 4.10 shows that the A1 neurons

normally respond to the onset syllable with one or occasionally with two bursts